Intro

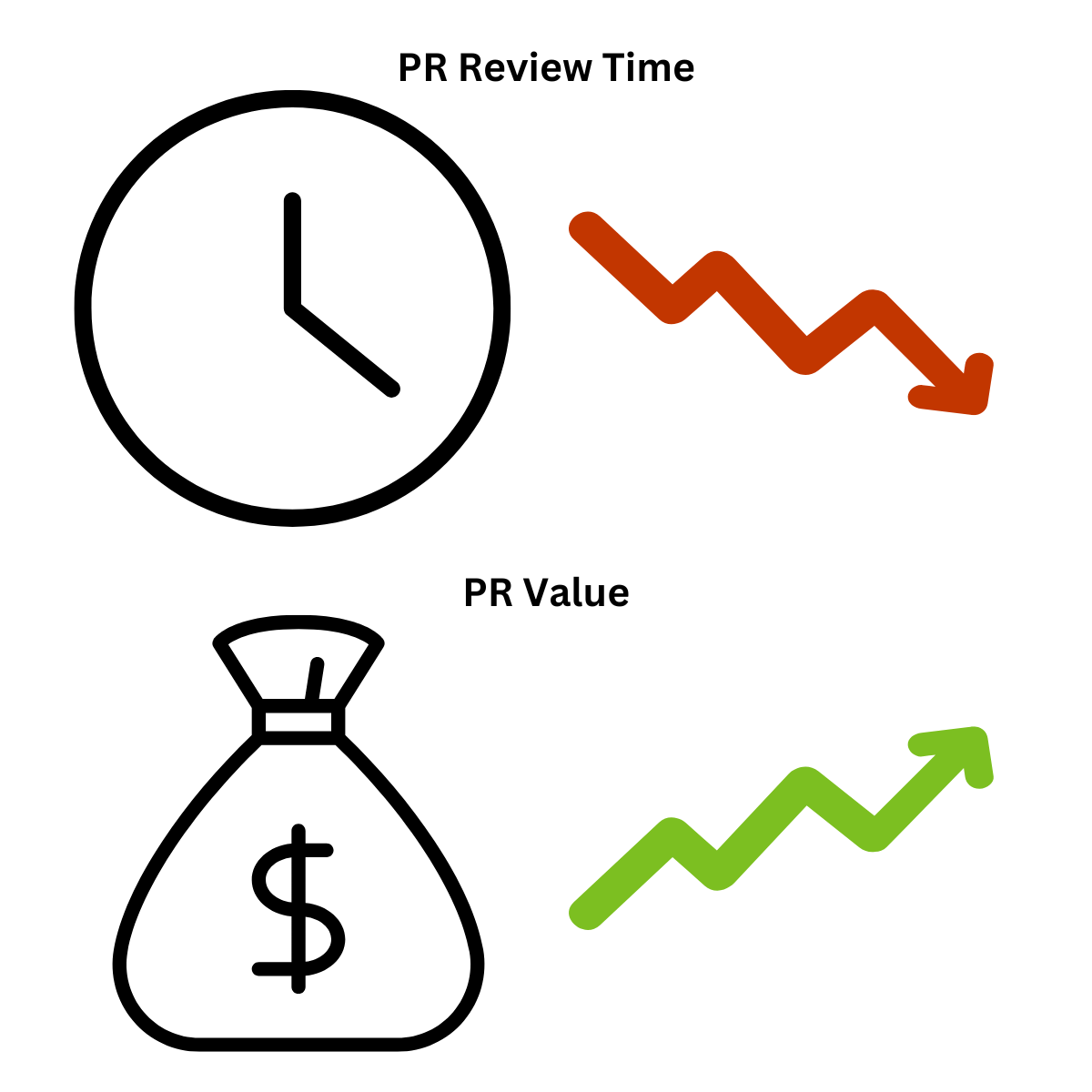

In part 1, I wrote about the value of doing a cost/benefit analysis for code reviews. The main cost is time. In this post, I will explore ways to minimise cost, while also increasing review quality.

Let’s start with the single most valuable point. The PR overview.

Standardise the PR overview

Make sure that everyone fills in the necessary information when opening a PR. Then, the reviewers will have the basic info they need to do the review. This can be easily done by using a PR template.

These are some fields that should serve as a starting point for most teams:

“Useful links”

Links to JIRA, related designs, documentation, etc

”How and why”

Any extra info that is not covered by the JIRA ticket. Why I implemented it this way, beware of this, etc

“How it looks like”

Some artefact that proves that PR does what it was supposed to do. This can vary per PR type. Some examples:

If it is a UI task, screenshot tests.

If it is a business logic task, unit tests.

If it is a functional feature, a video recording or E2E tests.

“How to test it”

A list of steps on how to test it:

It is available on dev/staging/prod environments

You need this type of account and these credentials

These are the actual steps to test it

Just by adding the How it looks like section, we saw significant improvement in quality. People had to prove their PR does what it claims. This forces you to think about whether you missed something beforehand. It also enables sharing quickly what this PR does and keeping a useful record.

The How to test it section eliminated many common back and forths:

“Hey man, what do I need to test here?”

“Is it available on staging?”

Starting with these fields you can iterate and add what makes sense to you. Some other field ideas: components affected, environments tested on, notes for QA etc

The key point here is to make sure everyone respects this. Will your team take a blood oath to do it? Will you need a regex validation check on your CI? Whatever works for you. For us it was the latter.

BTW I suspect you do have a standard format for your PR titles, right? If not, you can start with something like:

[ticket no][feat|fix|chore] PR Work description. →

[#112][feat] Add network requests interceptor

Moving on to the second high value/low effort action point. Keep PRs small.

Kill the monster PR

Huge PRs take forever to be reviewed. Why? Because no one likes them. I’d rather do a JIRA epic breakdown instead. Ok, I lied. I dislike both equally. If you want your PRs reviewed on time, keep them small. Be selfish.

“But the functionality needs to be all there for the feature to work.”

Well, that’s not true. You can use a feature flag for that. Protect your code with a feature flag and merge small PRs with pieces of functionality. If this is complex, you can also resort to feature branches.

I suggest verifying PR size at the CI level. Especially if you are a big team.

Otherwise, you might keep repeating the same discussions.

Since we are talking about small PRs, what about small, meaningful commits?

On small commits

Small commits are high effort, but often low value. An unconventional opinion I heard from a friend and stuck with me . Let’s see the pros and the cons of small commits.

Pros

The reviewer has a place to start the review from. And he sees small chunks instead of a pile of files.

Cons

You need to start with the commit structure in mind. And even then, the code that you fitted within a commit might change in the upcoming commits. So the reviewer might need to re-check the same code.

Can we get 80% of the value of small commits with 20% of the effort?

Well, just keep PR smalls and describe the thought process in the PR overview:

“My thought process was [this]. I suggest you start checking [this file] and [these unit tests] to understand how it works and then check [here] where it is being used.”

Providing context on PRs, is a real time saver.

On providing context

The events in this story are fictitious and any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental:

I see a weird thing on the PR.

I check out the code to see how it can be improved.

I send a solution blueprint as a comment, only to get this answer:

“Ah yes, I tried this already but it did not work because of this super-weird issue in the platform/library/backend”

Time spent - 25 mins

Value gained - 0

Providing context can help save time and get meaningful feedback.

If you

had to do something weird because the “normal” way did not work

copied a solution from somewhere

crafted a next-gen solution out of heavenly inspiration

please mention it in a comment.

Time spent - 2 mins

Value gained - 23 mins of the reviewer playing ping pong in the office

Now that I’ve finished the prep work I am officially ready for the first reviewer.

ME.

Be your own reviewer

“Oops, yes I missed that”

“Yep, forgot to delete these local files”

The more of these you have in the review, the less important issues the reviewer will spot. There is some known quote that a reviewer will always spot a fixed number of bugs, no matter what.

Major Warning

For the same reason I make refactorings standalone PRs. I learnt this the hard way.

70% of production incidents I have seen, were due to unnecessary refactorings done within a feature PR. Ok, I made this number up, but it was really high.

So, before appointing a reviewer I always do a first pass myself.

It is the honest thing to do after all.

The diff watcher

While reviewing my code, I always keep an eye on the change diff.

I wonder how I can keep the changes to a minimum. Why?

Let’s say I add a conditional check to a part of the code. Even though I added one line, in the PR diff it would appear like forty lines changed. Because of the updated indentation. The reviewer would then have to check all the lines one by one to verify what changed.

Two general solutions to that:

Solution 1

Just mention it to the reviewer.

“Hey, I only added this line. The rest I did not touch”

Solution 2

Craft your solution in a way to leave old code untouched. Sometimes an overkill, but it could help if you want to be surgical with the changes you make. Especially if you want to work effectively with legacy code.

And now that you finished your own review, you are finally ready. You have crafted a thoughtful PR and you assign an actual reviewer.

Only to find out that all this effort was for nothing.

The one where it all went wrong

Soon enough, you get a DM from the reviewer. You jump in the call only to find out that your solution has some major problem. You went the wrong direction. Now, you have to start from scratch.

Some reasons why this could happen? You lacked context. You didn’t have the technical experience. Or you just made the wrong call. It happens to everyone.

One way to avoid this, is to do a touch base with the reviewer, before starting any coding. Write down the outline of your solution and ask for a thumbs up.

You don’t have to always do this. But it makes sense for complex technical tasks or areas you lack context. And it connects well to the next point.

The PR should not be an afterthought

It pays off to keep in mind that your code will end up in a PR, from the start of the development process. Here's what the ideal me would do:

If the task requires it, I would ask for some feedback on the PR direction. I would then think about how I can break my task to multiple PRs. I would break it into small commits, only if that is easy to do. In the meanwhile, I would keep an eye on the diff changes. I would check them locally after each commit.

Opening the PR should not be an afterthought. It should be integrated into the coding process.

Finale

As with all practices, seek for balance.

Big, sloppy PRs are a notorious problem for most teams.

But don’t take it to the extreme and spend one hour to create “The Perfect PR”. There are no awards for that. My wife had me take down the one I printed for myself.

If you strike the right balance, PRs will be faster and more pleasant for everyone. A nice side effect is that PRs will stand as true reference points for the evolution of the code base. Numerous times we needed specific context on why and how we did something months ago. And the PRs had our back.